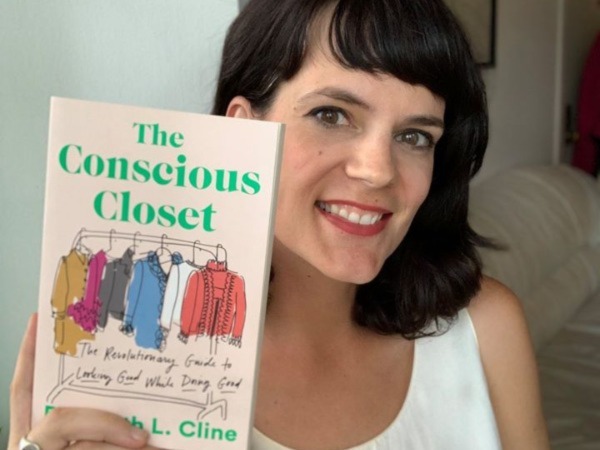

“If you want to change the world, there’s no better place to start than with the clothes on your back and the shoes on your feet.” So says Elizabeth L. Cline in her book, The Conscious Closet: The Revolutionary Guide to Looking Good While Doing Good (Penguin Random House, 368 pages).

According to Cline, the apparel industry accounts for 3% of the world’s economy, 8% of its carbon emissions, and a third of the microplastic polluting our oceans. It employs hundreds of millions at less than a living wage and is a leading consumer of water and toxic chemicals. The book covers a lot of ground in six sections, providing education on rightsizing your wardrobe, quality over quantity, staying fashionable, the impacts of different textiles, maintaining your clothes, and social activism.

Cline shares that most of us use just 30% of the hundreds of clothing items we own. Depending on your personality, she suggests you may get by equally well with a wardrobe of 50 items or less as a minimalist, 250 items or more as a fashion seeker, or somewhere in between if you are more traditional. While the process begins with a clean-out, she encourages a slower, more thoughtful process than other minimalism and decluttering books, focusing on finding a productive new home for your cast-offs. Donating to charity no longer provides the absolution it once did to avid fashionistas. Over the past 15 years, used clothing exports from the U.S. have tripled to 1.7 billion pounds a year. In Ghana, a leading importer of used Western clothing, 40% of imported used clothing is of such poor quality and low value that it is immediately landfilled rather than used.

“The majority of fashion’s environmental impact on the planet happens while manufacturing textiles. Buying sustainable materials and educating ourselves about what defines an eco-friendly textile are two powerful ways we can help reduce fashion’s footprint.”

Elizabeth L. Cline

To become more “conscious” about our closets, Cline encourages us to take “a fashion fast,” a complete and intentional break from buying new clothes for a set period. Use the break to evaluate past spending habits, repair existing clothing, and shop that unused portion of your wardrobe. You can even take a capsule wardrobe challenge where you try to create new outfits from minimal clothing items. Cline goes on to explain how secondhand or even full-price clothes of superior quality can save you money in the long run. Most clothing is now designed to be sold at a price low enough that a consumer will not give the purchase much thought, something called the “impulse threshold.” To get the cost below that point, manufacturers engineer the quality out of the item. One way they do this is to replace expensive natural fibers with less expensive synthetic fibers. After learning to evaluate quality, the reader learns how to construct a wardrobe that meets their needs. A limited number of colors, prints, and styles that mix and match easily form the core of any wardrobe, usually about 70% of the items. Accents bold in color, print, or style can make up about 30%.

Buying used is always preferable to purchasing new from an environmental perspective. Resale options have expanded from local brick-and-mortar thrift and vintage stores to online options that are local or worldwide. Cline reviews the pros and cons of each in detail. She also explores how renting clothes for a single occasion or even your entire wardrobe can be an environmentally and economically sound choice for a fashion seeker with a demanding work and social calendar.

In part four, she details the good and bad sides of the top seven fibers used today. Polyester is made from the same plastic used to make beverage bottles. It accounts for just over half of all fiber worldwide. Its production is energy-intensive, and synthetic fabric is the source of just under 35% of microfibers found in the ocean. Cotton, which accounts for 24.5% of fibers produced, uses a lot of water relative to other fibers — about 2,200 gallons go into every cotton T-shirt. This impact is amplified because 60% of all cotton is produced in areas where water is scarce. In addition, 6% of all pesticides used in agriculture go into cotton production; no other crop exceeds this. The impacts of viscose/rayon, leather, wool, linen, and silk are also detailed. For each of these leading fibers, there are safer, less toxic, and more sustainable options. The process of finding and evaluating those options is outlined in detail. The author also provides guidance on evaluating an individual brand or retailer’s performance in environmental stewardship and labor practices.

After the manufacture of textiles, laundering clothes has the second highest environmental impact of any part of the life cycle of clothing. U.S. washing machines use 6 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually, and U.S. clothes dryers use 60 billion, ten times as much. Cline suggests we wash our clothes less often, wash on cold when possible, and line dry as a rule. She provides details on “non-gross” ways to accomplish this and dramatically extend the life of our clothing in the process. There is also a section on clothing repair that will give you the confidence to mend and repair your clothes. Even if you don’t know a running stitch from a ladder stitch, you will learn how to replace buttons, close split seams, apply patches, and even darn wool sweaters.

“The bigger fight to fix fashion depends on our coming together to build a movement for change,” according to the author. Working conditions, safety, and income for as many as 75 million workers in the world’s textile, garment, and footwear industries vary dramatically. She outlines some past horror stories and current conditions in countries where most of that work is now performed. She provides a framework for joining others to pressure brands toward more transparency and eliminating “sweatshop” working conditions for those millions of workers who help keep us clothed.

This fascinating and detailed book helps the reader take individual actions and join with others “to advocate for widespread change so that ethical and sustainable fashion becomes the way of the world.”

Image courtesy of Elizabeth L. Cline